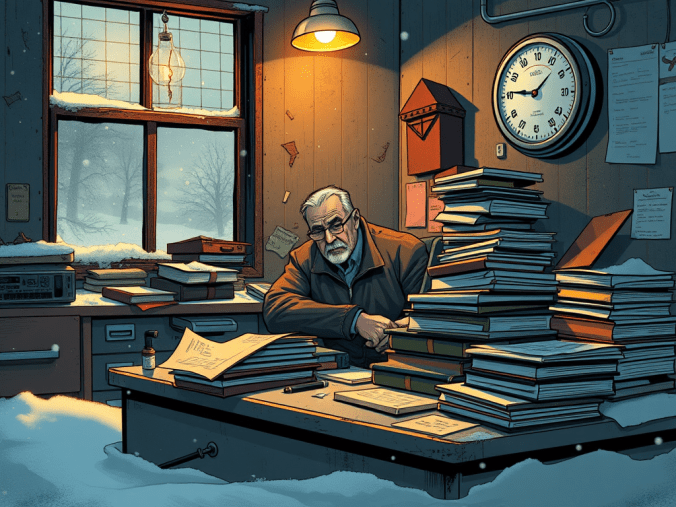

The office of the Pines Trailer Park hadn’t seen a proper repair in fifteen years. Ed Scott Ruje sat behind a metal desk scarred with cigarette burns and coffee rings, his breath visible in the frigid air. The wall thermostat read 52 degrees. Ed considered this generous.

He wrapped his thin jacket tighter and returned to his ledger book, tallying the month’s rent with the grim satisfaction of a man counting his victories. Outside, December wind rattled the loose siding he’d “fixed” last spring with duct tape and optimism. The duct tape had held. The optimism had not been necessary.

A knock interrupted his calculations.

“It’s open,” Ed called, not looking up.

Bobby Davis entered, work boots leaving melted snow on the stained carpet. Bobby was forty-two but looked older, his face weathered by years of patching trailers with inadequate materials and inadequate pay. He held his baseball cap in both hands.

“Mr. Ruje, I wanted to talk to you about Margie Thompson’s eviction notice.”

“What about it?” Ed made another notation in his ledger. “Woman’s three weeks late on rent. Notice is standard procedure.”

“She’s got leukemia, sir. The treatments—”

“Not my problem.” Ed looked up briefly. “She should’ve thought about that before she got sick.”

Bobby’s jaw tightened. “She’s seventy-three years old. She’s lived here forty-two years.”

“Then she should know better than to be late on rent.” Ed returned to his numbers. “Eviction stands. She’s got until January first.”

“That’s barely a week away. It’s Christmas Eve, Mr. Ruje.”

“Christmas is just another day, Bobby. Bills don’t stop for holidays.”

Bobby stood there a moment longer, hope dying in his eyes. Ed had seen that look before. He’d gotten good at ignoring it.

“There’s one more thing,” Bobby said quietly. “It’s about Timmy. The doctor says—”

“If you’re about to ask for an advance on your wages, the answer is no.” Ed didn’t look up this time. “You get paid on the first like everyone else.”

“I wasn’t asking for an advance. I was just… I thought you should know he’s getting worse. The medical bills—”

“I’m not a bank, Bobby. I’m not a charity. I’m a trailer park manager, and you’re my handyman. That’s where our relationship begins and ends.” Ed made a show of checking his watch. “Don’t you have that leak in trailer seven to fix?”

“Yes, sir.” Bobby’s voice was hollow. “I’ll get right on it.”

“Use the duct tape, not the good stuff. And make it last.”

After Bobby left, Ed allowed himself a small smile. Fiscal discipline. That’s what separated successful men from failures. His father had died broke, and Ed had learned from that mistake.

The office door banged open without warning.

“Uncle Ed!”

Rocky Martinez burst in, carrying a foil-covered casserole dish and wearing an aggressively cheerful Christmas sweater. At twenty-eight, Rocky had his mother’s optimism and, Ed thought sourly, her inability to take a hint.

“Brought you some tamales and enchiladas,” Rocky announced, setting the dish on Ed’s desk. “Mom’s recipe. Well, technically Abuela’s recipe, but Mom perfected it. Thought you might want some Christmas Eve dinner.”

“I don’t celebrate Christmas.”

“Yeah, you say that every year.” Rocky grinned, undeterred. “And every year I remind you that Mom made me promise to look after you.”

“Your mother’s been dead six years.”

“Promises don’t expire, Uncle Ed.” Rocky’s smile faltered slightly. “She said you had no sense of your own. Said someone needed to make sure you didn’t disappear completely into that ledger book.”

Ed felt an unwelcome pang that might have been guilt or indigestion. Denise had been the only person who never gave up on him, even after the betrayal, even after he’d pushed everyone else away. She’d visited every Sunday until the cancer took her, bringing food he wouldn’t eat and conversation he wouldn’t participate in.

He’d skipped her funeral. Too busy with park maintenance.

“I’m fine, Rocky. Don’t need looking after.”

“Sure you don’t.” Rocky glanced around the freezing office. “You know, I could get you a space heater from the store. Employee discount.”

“Waste of electricity.”

“Right.” Rocky headed for the door, then paused. “We’re having dinner at six tomorrow. Nothing fancy. Just me, Maria, and the kids. You’re welcome if you want to come.”

“I won’t.”

“Figured. But the invitation stands. It always stands, Uncle Ed.” Rocky opened the door, letting in a blast of cold air. “Merry Christmas.”

After Rocky left, Ed stared at the casserole dish. The foil was still warm. He pushed it aside and returned to his ledger.

Twenty minutes later, another knock.

“Now what?”

Two women entered, bundled in threadbare coats. Ed recognized them as residents from the east side of the park. The younger one, Sandra, worked at the laundromat. The older one was Helen, the self-proclaimed Italian chef who’d once tried to give him a spaghetti wreath at the potluck. He’d declined.

“Mr. Ruje,” Sandra began nervously, “we’re collecting donations for a sick child in the park. Medical expenses. We thought—”

“You thought wrong.” Ed didn’t bother looking up. “I don’t do donations.”

“It’s Christmas,” Helen said. “Surely you can spare—”

“I can spare nothing. I have bills, expenses, maintenance costs. You want to donate? Donate your own money.”

“We are,” Sandra said quietly. “Everyone’s giving what they can. We just thought, since you manage the park—”

“Since I manage the park, I have more expenses than any of you. The answer is no. Close the door on your way out.”

They left in silence. Ed made another notation in his ledger. The numbers always balanced. Numbers were reliable. People were not.

At eight o’clock, Ed locked the office and trudged through the snow to his trailer—a single-wide at the back of the property, tucked behind the dumpsters. Appropriate, he thought. He didn’t need much space. Space was wasted on people who filled it with sentiment and unnecessary possessions.

Inside, his trailer was as cold as the office. He turned on a single lamp, heated a can of soup on the hot plate, and ate it standing up while reviewing the next month’s maintenance schedule. Trailer seven still had that leak. Trailer twelve needed a new window, but Ed had found a sheet of plexiglass and some weather stripping that would do the job for a fraction of the cost. Trailer eighteen—

The lights flickered.

Ed looked up. The single bulb dimmed, brightened, then dimmed again. The hot plate clicked off.

“Damn breaker,” he muttered, setting down his soup.

He crossed to the small electrical panel by the door. The breaker switches were all in the correct position. He flipped the main switch off and on. Nothing happened. The lamp stayed dim, pulsing with a weak, irregular light.

Then he saw it.

In the dim, flickering glow, a face appeared on the breaker box. Not a reflection—a face forming in the metal itself, as if pressed from behind. Angular features, sunken eyes, a mouth frozen in a silent scream.

Marley.

Ed stumbled backward, his hip hitting the small kitchen counter. The face remained, growing clearer as the light continued its sickly pulse. Marlon “Marley” Jacobs, his former business partner, died twelve years ago. The man who’d helped destroy Ed’s dreams. The man who’d introduced Ed to the businessman who’d swindled them all.

“Not possible,” Ed whispered.

The face in the breaker box moved. The mouth opened, and though no sound came from the metal, Ed heard a voice—rusty, distant, like wind through corroded pipes.

Ed.

“I’m hallucinating. Bad soup. That’s all.”

The lights went out completely. In the absolute darkness, Ed heard a sound like chains dragging across gravel, like metal scraping metal. Something rattled. Something clanked. Something hissed.

Light flooded the trailer—not from the lamp, but from a sickly green glow that seemed to emanate from the air itself. And there, standing in Ed’s tiny living room, was Marley.