Introduction

The United States emerged in the 20th Century as an innovator and an engine of change. But as the saying goes, “All progress involves change, but not all change is progress.” Thus, the United States found itself fighting against free expression while also promoting it. Case in point, before Hollywood became “woke” (whatever that means), it was anything but. Tinseltown perpetuated racist and antisemitic themes. Later, Congress got into the act, using paranoia and false conspiracies to destroy lives and careers to sustain an ideological agenda by muzzling the truth under a mountain of lies. At the heart of this conflict was the First Amendment and efforts to challenge the guardrails of the rights therein. These challenges have increasingly found their way into the courts, ultimately the Supreme Court.

New Century — New Challenges

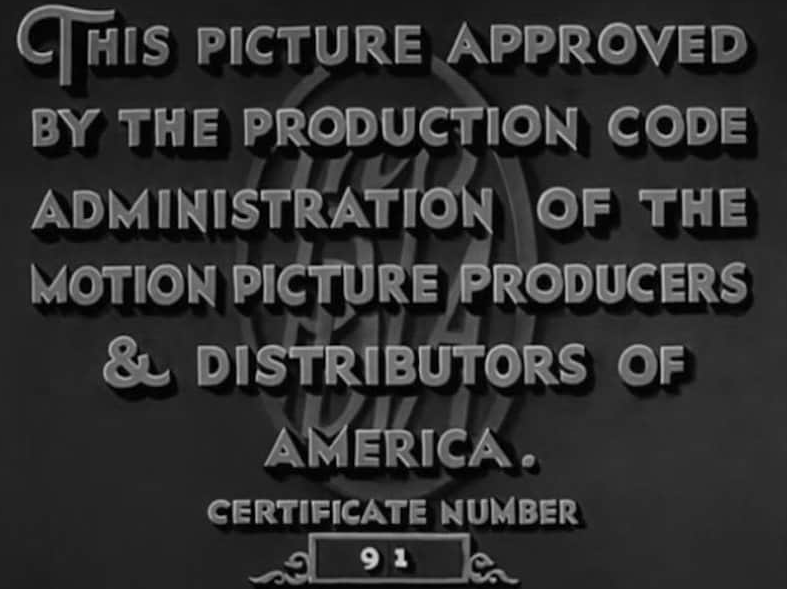

The 20th century saw a new wave of censorship, initially focused on newly emerging mediums like film. The Motion Picture Production Code, which was adopted in 1930, prohibited a wide range of content from films, including sex, violence, and profanity. The government did not enforce this code, but the film industry voluntarily adopted it to avoid government censorship. What is not addressed explicitly by this code is the complicity of Hollywood in perpetuating the status quo of Jim Crow in the South. By indirect means, the entertainment industry perpetuated the oppression of minorities by reinforcing stereotypes and racist themes.

The dawn of the Cold War unveiled a new wave of censorship aimed at suppressing information about communism. Libraries were targeted, and books and magazines considered to be communist or subversive were often banned. Lives and livelihoods were ruined by Hollywood blacklists and the activities of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC).

The government also censored information about the Vietnam War or outright lied (as revealed by the Pentagon Papers), and many journalists were arrested for reporting on it.

There have been several challenges to censorship in the United States recently. The Supreme Court has ruled that the First Amendment does not protect obscenity in two cases, Roth v. United States (1957) and Miller v. California (1973). Yet the Court also ruled that schools and libraries cannot censor materials simply because they are offensive to some people.

In the case of Miller v. California (1973), the Supreme Court established a three-part test for determining whether material is obscene and, therefore, not protected by the First Amendment. The test is as follows:

(Test 1) Whether the average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest, meaning that it “arouses a lascivious, shameful, or morbid interest in nudity, sex, or excretion.”

The Court also said the work must be “patently offensive” to the average person, applying contemporary community standards.

- In other words, a work appeals to the prurient interest if it is sexually suggestive in a way that is intended to arouse lust or sexual desire. It must also be offensive to the average person, meaning that it would be in bad taste by most people. Which means the standard means different things to different people. Such a nubile definition led Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart to observe in 1964, “I know it when I see it.”

- Note that the prurient interest is different from the sexual interest. Everyone has a sexual interest, but not everyone has a prurient interest. The distinction is that prurient interest is a sexual interest that is excessive or unhealthy.

- The concept of the prurient interest is controversial, and no universally accepted definition exists. However, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Miller v. California provides some guidance on what it means for a work to appeal to the prurient interest objectively.

(Test 2) Whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law. Given the patchwork of laws in the United States, work can be acceptable in one part of the country but banned in another.

(Test 3) Whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

What constitutes “serious” value is an opinion, and no single definition is universally accepted. However, some factors that courts may consider when evaluating whether a work of art lacks serious value include:

- The work’s artistic merit. Does it demonstrate skill, creativity, and originality?

- The work’s literary merit. Does it tell a story, explore a theme, or offer insights into human nature?

- The work’s political or social commentary. Does it make a significant contribution to the public discourse?

- The work’s scientific value. Does it provide new knowledge or insights about the natural world?

Note that the lack of serious value is not the only factor that can make a work of art obscene. However, it is often a critical factor in determining whether a work of art is obscene.

In the case of a work of art that lacks serious value, the government may be able to restrict its distribution or exhibition. However, the government must show that the work of art is obscene in the legal sense and that it is necessary to restrict its distribution or exhibition to protect public morals or the health or safety of the community.

If a work meets all three criteria, it is considered obscene and not protected by the First Amendment. However, if a work does not meet all three criteria, it is protected by the First Amendment, even if it is offensive to some people.